You have to hand it to the marketing team behind Longlegs. They got the job done.

But did they understand the assignment?

With early reviews comparing the film to seminal thriller The Silence of the Lambs and others suggesting it was the ‘scariest movie of the decade’, director Oz Perkins, son of horror icon Anthony ‘Norman Bates’ Perkins, had a lot to live up to. In the event, whilst Longlegs offers an atmospheric and at moments truly frightening experience, I can’t help but feel that this was a victim of its own hype.

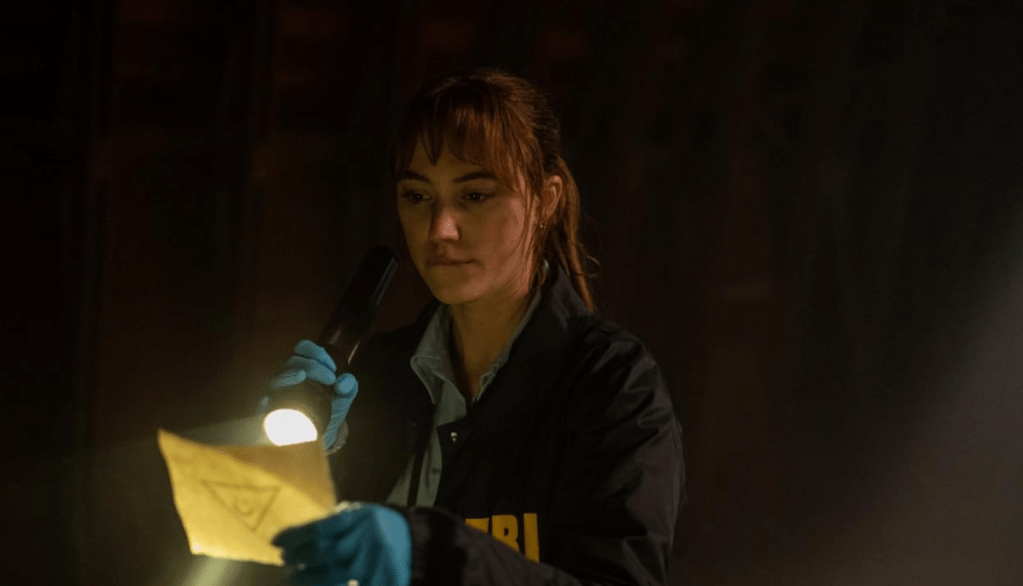

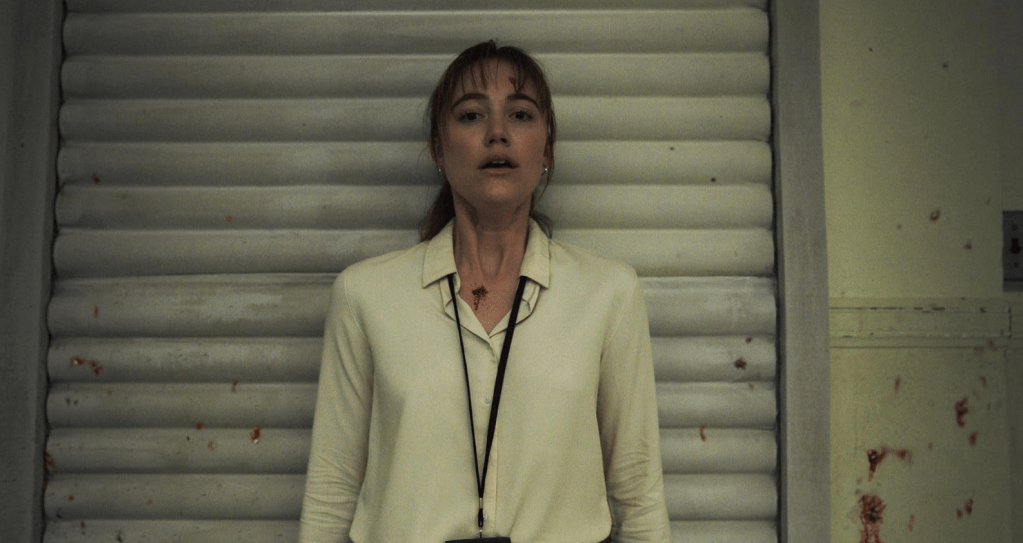

Maika Monroe (Watcher, It Follows) plays an FBI agent, Lee Harker, whose almost-miraculous intuition for tracking down killers quickly gets her placed on a decades-long case despite her relative inexperience. Ushered onto the cold-case by her boss Agent Carter (Blair Underwood), Harker is tasked with trying to make sense of a series of near-identical murders that all saw loving families degenerate into the most violent and abject bloodshed when each father brutally kills his wife and children before ending his own life in an apparent murder-suicide. These crimes, however, share a few connecting threads: each family has a daughter whose birthday falls on the 14th of the month, and despite the seemingly ‘clean’ crime scenes that do not indicate the presence of any third-party, a letter is left in each instance signed by ‘Longlegs’.

From the outset, Perkins shrouds the titular killer (played by Nicolas Cage) in mystery, deliberately fragmenting his body through claustrophobic cinematography in the film’s hypnotising opening sequence, keeping Cage’s face (and significant prosthetics) just off-screen. In this regard, Perkins/Cage render Longlegs a truly sinister figure, with each further encounter allowing us additional snippets before his full unsettling appearance is finally made apparent. Stylistically, Longlegs is an engrossing watch, with editing, camerawork and sound design all highlighting Perkins’ willingness to experiment with the form and expectations of the horror genre. That said, it is perhaps because of the film’s evident focus upon its aesthetic that its narrative gets somewhat lost in the mix.

Neon’s ARG marketing campaign for the film, featuring disturbing voice messages left by Longlegs, cryptic video teasers, and a 90s-era website purporting to serve as a blog charting the history of the ‘Birthday Party Murders’, all positioned the film as something closer to a horrific, but relatively grounded thriller; these crimes were an enigma to be deciphered. Indeed, for these sites and teasers, as in the film itself, the killer utilises a linguistic code, much like the Zodiac killer, his intent and goals seemingly ‘understandable’ as long as you can figure out the puzzle. These elements of its marketing, as well as the conceit of an FBI agent tasked with tracking down a prolific serial killer, established an expectation (at least from my perspective) that Perkins’ film would, even if horrific in its content and imagery, be predicated upon the objective reality of genre predecessors such as Zodiac, Mindhunter, Se7en, and yes, Psycho.

The fact that, SPOILER ALERT, Longlegs actually hinges upon a relatively unexpected supernatural conceit somewhat lessens the impact of the film’s final act, where such machinations are placed front and centre. In essence, the film pulls the rug out from under you, telling us that any attempt to rationalise or understand the killer is impossible. The rules are broken, if in fact they ever existed. This revelation put me in mind of Raymond Chandler’s thoughts on mystery fiction, praising works that ‘[fool] the reader without cheating’ them whilst criticising those that don’t play fair.

In a way, I do feel cheated by Longlegs. Perhaps I should have realised the film’s game sooner: the opening credits, the names of its cast and crew plastered across a blood-red backdrop to the blues guitar strumming of T-Rex’s ‘Jewel’ disarms the initial shock we have experienced in the film’s opening minutes with a kind of pulpy sleaze which empties out some of the ‘seriousness’ of the piece. Similarly, when Cage’s performance is given more visibility, the film begins something of a tightrope walk that continually threatens to collapse into farce. In contrast to the sinister but often disturbingly understated performances of John Carrol Lynch in Zodiac, or Cameron Britton in Mindhunter, Cage’s sometimes cartoonish creation shares more in common with the carnivalesque excess of Jack Nicholson’s Joker, complete with his own catchphrase – ‘Hail, Satan’.

Despite these reservations, I still enjoyed Longlegs as a cinematic experience, and I suspect a second viewing will reap more insight and appreciation of Perkins’ vision, now that I have an understanding of the film beyond the perhaps deliberately skewed version crafted by the film’s marketing department.