As an alumni of Studio Ghibli, Yoshiyuki Momose’s film The Imaginary will inevitably be compared to that powerhouse of Japanese anime and its founding directors, Hayao Miyzaki and Isao Takahata. For better or worse, Momose’s film, an adaptation of the children’s novel of the same name by A. F. Harrold, does distinguish itself from these predecessors, although in a manner that loses some of the idiosyncrasies of its cultural context.

The film tells the story of Rudger, an imaginary friend plucked from the mind of a young girl called Amanda. The opening few minutes see the pair embark on flights of fantasy and playful adventure, with Momose’s animators bringing the otherworldly and surreal delights of a child’s imagination to life. It is in sequences such as these, seen throughout the film, that Momose most readily wins his audience over, echoing the unique world-building and fantastical imagery of anime films like Paprika, Spirited Away, or more recent hits like Promare or Belle.

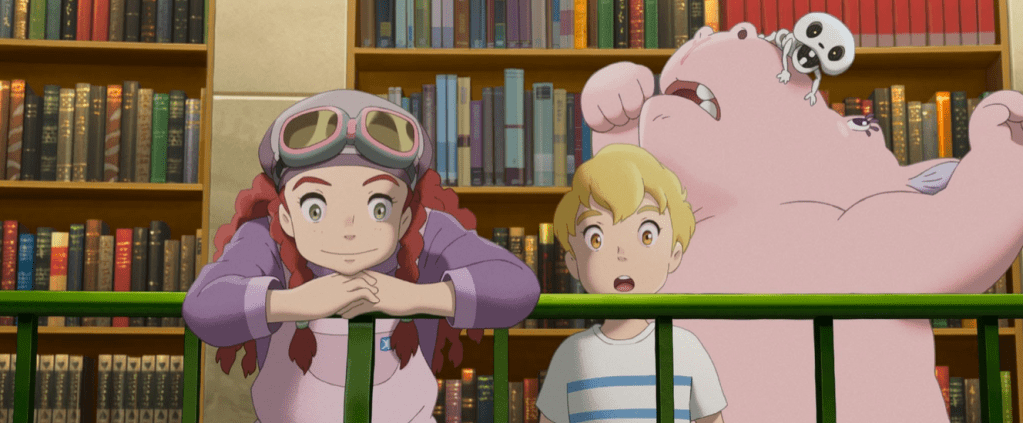

Amanda lives with her mother in a family-run bookshop, the film repeatedly championing the revolutionary power of reading and literacy amongst children (once the larger cast of the imaginary world is uncovered, it is revealed that orphaned imaginary friends are able to survive by drawing power from the significant imagination collected upon the shelves upon shelves of books in a local library). In the bookshop’s attic, Amanda and Rudger enjoy each other’s company after school, with the latter always excited for his creator to get home so they can undertake another adventure. However, a chance encounter with an older man who seems to have his own imaginary friend, a ghostly child reminiscent of Sadako from Ringu, places both Amanda and Rudger in danger, with the man – known as Mr. Bunting – revealed to be a harvester of the imaginary, a practice that prolongs his own mortal life at the expense of entities like Rudger.

An adaptation of the aforementioned British novel, The Imaginary maintains the source’s UK setting, with the film’s artists rendering the aesthetic and architecture of contemporary suburban Britain beautifully. There’s something slightly uncanny about this choice (perhaps only from the perspective of this British viewer!) with such scenes not usually serving as a backdrop for Japanese animation. That said, the film’s mise en scène is not the only element which feels distinctly transnational. In many ways The Imaginary comes across as the product of Western animation and storytelling, its transnationalism feeling somewhat commercial; as a Netflix release, The Imaginary feels at times consciously designed to appeal to a broader, international marketplace, in turn losing some of the cultural specificity and meaning that, looking for example to something like Miyazaki’s adaptation of Welsh children’s novel Howl’s Moving Castle, other filmmakers working within this form are able to maintain.

Elements of its narrative and characterisation are also blatantly derivative of the Pixar school, most notably films like Toy Story and Monsters Inc. In its tendency toward over-exposition, Momose’s storytelling feels distinct from the enigmatic and often incredibly idiosyncratic narratives of someone like Miyazaki. Unlike films like Spirited Away, My Neighbor Totoro, or more recently, The Boy and the Heron, Yoshiaki Nishimura’s screenplay feels the need to continually spell-out and explain its most fantastical elements, in opposition to Miyazaki’s willingness to maintain fantasy and leave some elements unexplained or open to interpretation. And yet, despite this level of exposition, The Imaginary is simultaneously marked by a sense of inconsistency, with its in-world logic often bending or ignored entirely should the narrative require it.

Perhaps such concerns are unimportant, particularly given the key demographic of the film, although such an excuse would be dismissive of the intelligence of children as well as the ability of filmmakers like Miyazaki to craft both engaging and cohesive worlds. The Imaginary is beautiful to look at, but I suspect that its cultural longevity is less guaranteed.