John Carpenter’s famous slasher, Halloween, begins with an extended sequence depicting young Michael Myers preying on his family home. Shot from his point of view, the camera places us in the shoes of a killer, aligning us with his murderous gaze and as-yet-unknown motivations. In a Violent Nature is effectively this iconic scene writ large, stretched into a 90-minute thriller that, whilst interesting and subversive in some ways, has difficulty articulating exactly what it wants to say.

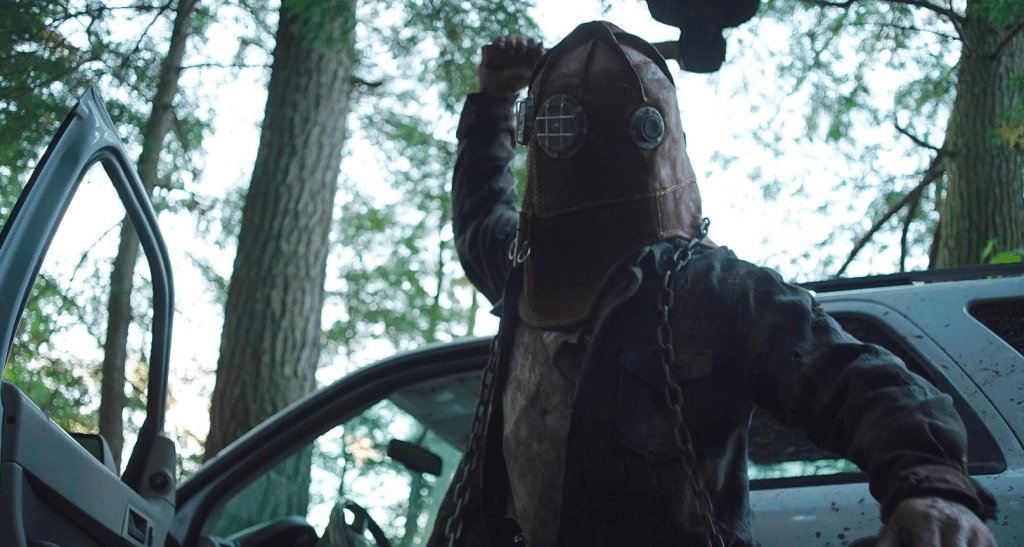

The film’s opening sequence introduces us to the killer of the piece, a hulking man who we come to know as ‘John’ (think Jason Voorhees: once human, but now an unstoppable, supernatural force). John re-enters the living world from a shallow grave in the footprint of an abandoned forest cabin, having been apparently summoned by a group of 20-somethings’ discovery of a mysterious golden locket hanging nearby. Now reborn and ready for action, John stumbles into the woods at a pace just above your average Romero zombie. He staggers through the underbrush, first finding a dead animal caught in a hunting trap. Finding the hunters’ markers used to signpost the trap, he retraces these steps to come across the hunters’ house, ambling up to the building whilst the hunter and a local park ranger bicker outside. In moments like this – as the camera follows John from behind as he slowly makes his way toward his target, director Chris Nash even jump-cutting through proceedings to move things along – In a Violent Nature begins its work highlighting the artifice and controlled structuring behind most slashers of this type.

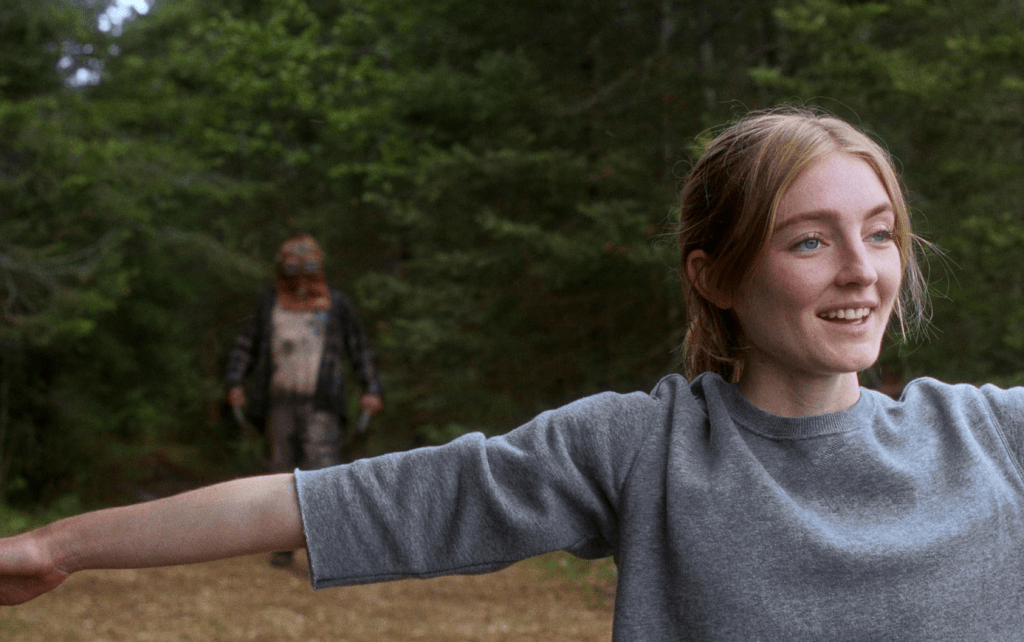

The film evidently sets its sights on the likes of Halloween, Friday the 13th, and The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, drawing attention to the mental gymnastics that must be accomplished in order to suspend our disbelief as viewers. Whilst Nash’s film isn’t primarily a comedy, its more interesting moments are those that I couldn’t help but read as comedic indictments of the clichés and conventions of the slasher sub-genre. How on earth are we meant to believe that Jason could have got the jump on that guy, walking leisurely up through the clearing in broad daylight!? At different moments in the film, as John tracks down and brutally kills the collective youths that have dared to defile his burial site and steal a treasured ancestral heirloom, his victims overlook John’s whereabouts mostly due to fluke and circumstance. In one instance John gets distracted by a shiny toy and sits himself down with his back to a tree trunk, whilst his next victims blunder obliviously in the background wondering how they could have possibly been outwitted by this sinister and deviously cunning force. Near to the final confrontation, a character anxiously taunts an unseen John, shouting into the woods – ‘What are you waiting for?’ – give John a chance, buddy, he’s still slowly making his way over, one lumbering step at a time from the last murder scene!

This self-aware critique of the sub-genre’s most recognisable tropes is perhaps more subtly communicated than an out-and-out meta-comedy like The Cabin in the Woods or Tucker and Dale vs. Evil. Indeed, from the film’s philosophising title to the director’s choice of aspect ratio – the boxy 1.33:1 – In a Violent Nature seems consciously evocative of a kind of ‘art-house’ aesthetic, imbuing the film with a pseudo-serious pretension to offset the video nasty formula the film is working to revise. But it’s a choice which never quite feels earned: the film veers from a seemingly meditative almost realist mode of narrative to moments of cartoonishly bloody spectacle ripped straight from the slasher sub-genre’s back catalogue of greatest hits. Simultaneously, its snail’s-crawl pacing, often picturesque depiction of the natural American forestland, and its final act subversion, opting for an extended conversation between the film’s obligatory final girl, Kris, and the local woman who saves her, seem to frustrate any notion of the film’s appeal to mainstream horror audiences. Yet, if one motivation of the film is to confront the engima of the subgenre’s central figure, Nash appears to lose his nerve at select moments, departing from the film’s central conceit – a slasher told from the POV of the killer – to spend time with the victims, seen for example in the aforementioned finale, as well as a midpoint campfire sequence that sees the assorted youngsters recite the local legend of the ‘White Pine Killings’ that John committed. Sequences like this offer little more than an exposition-dump, with Nash seemingly lacking faith in his audience to go without the kind of narrative decoration that would accompany and justify a ‘traditional’ slasher.

The film’s final conversation piece, which sees Kris’ saviour proclaim (believing that the final girl has simply been attacked by a wild animal in the woods) that ‘animals don’t get too hung up on reason. They just keep killing’, seems to serve as the film’s central thesis. Sometimes there’s no explanation for the killing that unfolds before our eyes, particularly in a slasher film. The slasher is a genre that is, first and foremost, a loosely assorted collection of set-piece kills, each designed to surpass the previous one in terms of gore and violence. In giving John a ‘reason’ in the form of the golden locket that belonged to his mother, an item he values as something of a personal talisman and one that he desires to get back, Chris Nash is perhaps highlighting the sub-genre’s inclination towards empty ‘macguffins’ as the cause and effect of the slasher’s killing spree. In doing so, however, does he not risk his own film becoming just as emptied of any such meaning in the process?