In the final moments of Warner Bros. Animation’s Justice League Dark: Apokolips War, an assortment of DC’s heroes are sat watching the sun set on their world and universe, having defeated the arch-villain Darkseid but at the cost of their own timeline and existence. Barry Allen (aka ‘The Flash’) is tasked with traveling back in time to reset the heroes’ lives, knowing full well that their continuity and existence will be sacrificed; that the stories and battles that have been fought and won will be wiped clean, the game pieces moved back to square one. Closing out the company’s animated ‘DC Universe’, Justice League Dark: Apokolips War marked the in-universe bridge between some sixteen films and the company’s rebooted slate of films resetting continuity and canon with 2020’s Superman: Man of Tomorrow.

I had fully expected Andy Muschietti’s long-awaited The Flash starring (the obviously problematic) Ezra Miller to facilitate a similar multiversal reshuffle for DC’s live-action franchise, clearing the deck for what is to come, with new Chief Executive Officers James Gunn and Peter Safran tasked with rebuilding the brand from the ground up. Instead, Muschietti’s film, an amalgamation of competing and often contrasting elements from the Snyder-era Justice League running amok with the decades-spanning history of Warner/DC’s franchise offerings and tangential adaptations, arguably leaves more questions unanswered.

This new film’s core premise essentially adapts one of the most significant Flash stories of recent years, 2011’s Flashpoint by Geoff Johns, which sees Barry Allen running back in time to prevent the murder of his mother, Nora, and to therefore free his wrongly accused father from incarceration. As with any time-travel narrative, things do not go to plan and Barry’s actions instead create a world in which the earth’s heroes (Batman, Wonder Woman, Cyborg, Superman, Aquaman) either don’t exist or have become villainous mirror images of the heroes that we know and love. Whereas in Johns’ story, Barry works alongside Thomas Wayne’s Batman (Bruce having been the ill-fated victim of the gunman outside of the Gotham theatre in this alternative continuity) to free an imprisoned Kal-El (Clark Kent/Superman) from power-restricting captivity, Muschietti’s film adopts the story’s foundational multiversal conceit to bring back Michael Keaton’s version of Batman (as seen in Tim Burton’s 1989 Batman and its sequel Batman Returns) whilst substituting Kara Zor-El, or Supergirl (brilliantly played by relative newcomer Sasha Calle) for Henry Cavill’s missing-in-action Clark Kent. Also in the mix, Muschietti adds an extra Barry Allen (again played by Miller in a dual performance), but one that, at least initially, does not have the powers of the Flash, instead enjoying, and perhaps taking for granted, the domestic bliss of a family life unmarked by tragedy and loss. The main difference or consequence of this universe, however, is that Superman is not around to fight and ultimately defeat rogue Kryptonian General Zod, played by the scowling Michael Shannon who was last seen (alive) in Snyder’s Man of Steel (2013). Cue Zod’s legion of behemoth spaceships and Kryptonian soldiers landing on earth in a bid to eviscerate humanity and establish the planet as a new Krypton with the aid of their terraforming ‘World Engines’. Alongside his multiversal doppelganger, Keaton’s Batman and Calle’s Supergirl, Barry Allen has his work cut out for him.

‘A Hot Mess’

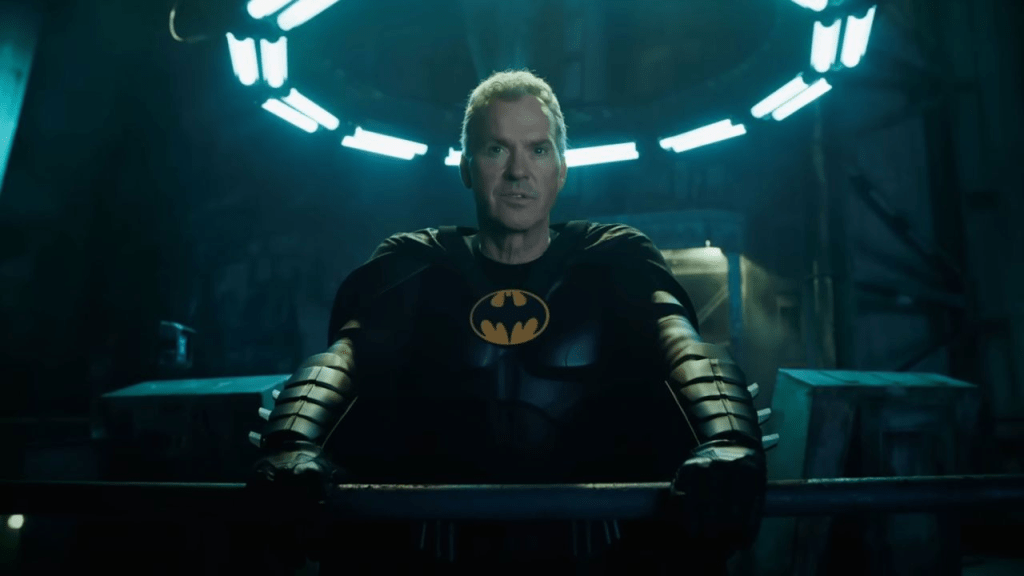

Prior to the film’s inevitable third-act smack-down, Barry tracks down this universe’s Bruce Wayne, a seemingly retired Batman now living alone as a bearded hermit in a decaying Wayne manor. Analogising these various timelines and strands of continuity as an intertwining bowl of spaghetti, Keaton’s Wayne summarises the multiversal situation in which they find themselves as a ‘hot mess’. It’s an unfortunate line, given how easily it can be replicated as headline fodder for cynical reviews of the film. In many ways, The Flash is just that – a hot mess – a Frankenstein amalgamation of different influences, re-shoots and executive notes resulting in a film feeling as tonally uncertain and as jarring in its construction as the idea of the multiverse itself. It should be remembered that the most significant multiverse event in the history of DC comics (other than the original ‘Flash of Two Worlds’ story) was the Crisis on Infinite Earths mini-series, which Marv Wolfman wrote as an attempt to steady the mess of DC continuity which had been plaguing the company’s comic titles. In a sense, The Flash attempts to do the very same, grappling with the ‘hot mess’ of DC’s live-action slate – its various offshoots, muddled continuities, disappeared actors and broken promises. As alluded to, what it lacks – and what I expected – was a moment that resets the clock to zero.

There’s a lot to critique here (all in good time), but let’s start with ‘the good’. Calle’s Supergirl is a force to be reckoned with, an up-and-coming actress with clear talent and magnetic screen appeal – I sincerely hope Gunn keeps her in the role for the announced Supergirl: Woman of Tomorrow. Similarly, Keaton’s return to the Batman character is charming in its nostalgia factor, and the actor is clearly having a good time in the role, echoing his much-quoted lines from Burton’s original films whilst sparring with what a modern superhero film can be (we’re past the days of Jack Nicholson’s Joker knocking over priceless antiques to the soundtrack of Prince). It’s also nice to see the return of Ben Affleck’s incarnation of Bruce Wayne, who we spend time with at the start of the film; whilst both Batman vs. Superman and (either version of) the Justice League are not without flaws (many, many flaws), I do think there’s a tendency to overlook how Affleck prospers in the cowl.

Miller, on the other hand, is more of a question mark. This is not the space to re-litigate the allegations and suspect behaviour that has marked the actor’s career in recent years (a career, I would be willing to bet, that is probably done and dusted following this film’s release). I will say though that, whilst adding further meat to the bones of their performance in Justice League, this version of Barry Allen is one that simply doesn’t resonate with me – Miller’s take being a socially-awkward geek often played for juvenile, slapstick laughs, more than any kind of serious commentary upon the potential neurodivergent aspects of the character that some have interpreted this version of Allen as embodying. This certainly isn’t the Flash of the original comics (the all-American jock-turned-scientist), or indeed, the best interpretation of the character seen on screen (do a lap of honour Grant Gustin!)

Madness of the multiverse

My main issue is with its execution of the multiverse concept to begin with. I should state now that I am not against the multiverse idea as others are – far from it. Some of the best science-fiction storytelling revolves around the possibility of alternative histories, parallel universes and the encounters that occur between them (the work of Michael Moorcock springs to mind, as does Stephen King’s Dark Tower series, films like Everything, Everywhere all at Once and Donnie Darko, TV series like Doctor Who, Dark and the best of the best – Community’s ‘Remedial Chaos Theory’ episode).

Instead, I am against its use as little more than a vehicle for cameo appearances from prior performers. Spider-man: No Way Home (2021) is a good example of this. Yes, the film offered a nostalgic, if slightly contrived, chance to celebrate the adaptative history of the Spider-man character’s 21st-century incarnations, allowing Holland to come together with both Toby McGuire’s and Andrew Garfield’s interpretations, respectively. But the manner in which it approached its narrative, facilitating their ‘entrances’ with a closed-down set in order to keep their casting under wraps and allowing a momentary pause for walk-on applause like Brad Pitt showing up on Friends highlighted its synthetic nature – prioritising star spectacle over storytelling. To give the film its credit, at least audiences (myself included) wanted to see McGuire and Garfield on screen again.

By comparison, The Flash’s attempt to echo this kind of ‘legacy’ celebration is a mixed bag. Yes, it’s good to have Keaton back, but have we really forgotten how much of a disaster Clooney’s turn at the character was back in 1997? [Spoiler Alert!] In The Flash, Clooney appears at the eleventh hour just before the credits roll as if his presence marks the ‘return of the king’ (surely Christian Bale would have garnered more of a reaction?) despite the fact that Batman and Robin notoriously saw the late director Joel Schumacher apologise to comic fans for what he had done to the character. Similarly, I’m not sure how a casual audience would respond to the presence of a de-aged Nicholas Cage donning the Superman suit he wore in test-footage for the quickly aborted Burton project from the 1990s. How about the homage to George Reeves’ black and white television incarnation, or the presence of Helen Slater’s Supergirl from the eponymous 1984 film that dramatically bombed at the box office? Allusions to a film that was never made, a box office disaster, and a 1950s television series surely aren’t topping any DC fan’s list of who and what they want to see on screen, are they?

Another issue is the film’s uneven VFX. As has been reported, this should never be thought of as a mistake or incompetence on the part of the VFX artists themselves, who are excruciatingly overworked and stretched to the limit within the industry, particularly when working for Marvel and DC projects. I think what makes the film more notable in this regard are the staggering discrepancies between what works and what doesn’t. Environmental effects and digital landscapes are phenomenally rendered, and its blend of digital cinematographic and VFX techniques alongside conventional in-camera work is routinely brilliant (I’m thinking particularly of the sequence that sees Supergirl regain her powers). The film also features, for my money, the most convincingly realised dual performance ever put on screen, with Miller’s two portrayals of Barry sharing a significant amount of screen time and never once stretching credibility. On the other hand, the film’s rendition of the ‘Speed Force’ – depicted here as a plastic two-dimensional praxinoscope straight from the hellish depths of the uncanny valley by way of a PS2 game’s cut-scenes – as well as its opening sequence of baby juggling antics (a scene that makes the baby monstrosity from Twilight look, somehow, comparatively photo-realistic) all work to undermine the realism and believability seen elsewhere.

All in all, The Flash offers some engaging moments of action and set-piece sequences but is frequently dogged by its uneven structure and tone. Reportedly, three different endings were written, with Gunn/Safran’s third-act being the one that made it to cinemas. This ramshackle approach was probably more due to external factors (DC/Warner’s implosion and changing of the guard, Miller’s off-screen behaviour and a requirement to foreground Keaton/Calle and other performers over the problematic lead actor) rather than Muschietti’s storytelling or directorial ability. In fact, it’s probably due to the director’s stamina and conviction that we have a film in theatres at all, even if the end result is messy (hopefully, Batman: The Brave and the Bold will allow the director a proper chance to shine in this genre). The final nail in the speedster’s coffin, however, was the fact that this was released within a week of Spider-man: Across the Spider-verse a film that fully exploits the potential of the multiverse conceit. The Flash never stood a chance.