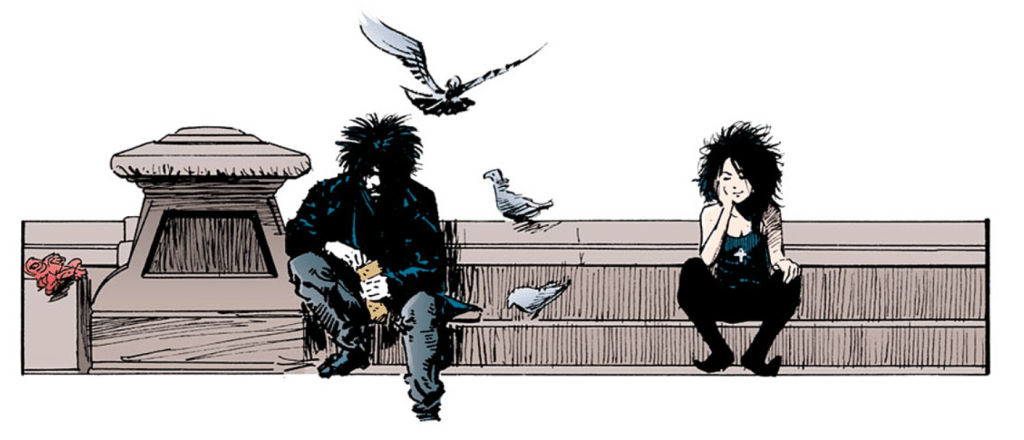

A key reason I love Neil Gaiman’s Sandman comics is that with each new issue, you never know exactly when, where and with whom you might find yourself. One chapter might play out like a video-nasty nightmare (’24 Hours’), another a treatise upon the nature of storytelling’s relationship to ‘truth’ (‘A Midsummer Night’s Dream’), or a vision of an alternate history of humanity (‘A Dream of a Thousand Cats’). Extended arcs, be it those collected in The Doll’s House or A Game of You, might offer further time with characters and stories that Gaiman allows you to explore in further detail, whilst simultaneously offering momentary interludes such as ‘Tales in the Sand’, a mythic narrative that can be fully enjoyed on its own but one that also furthers our understanding of Morpheus as a character.

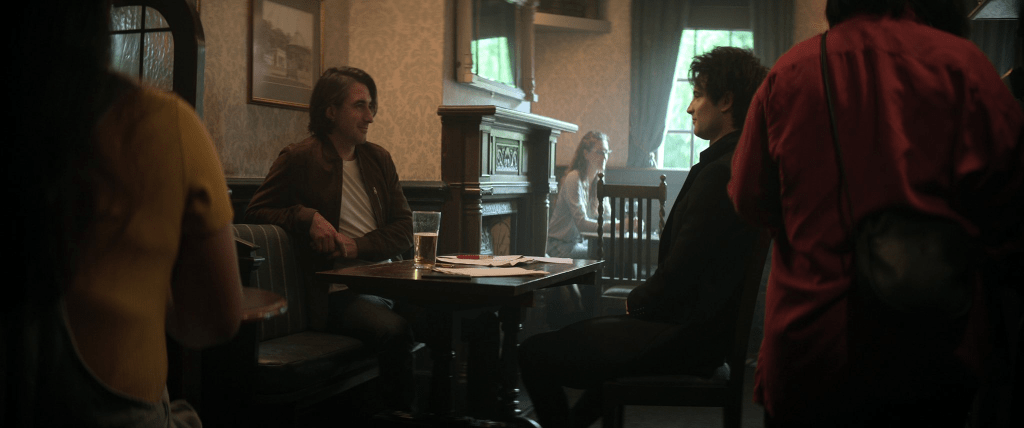

It is therefore both a joy and a surprise to discover that the long-awaited Netflix adaptation of The Sandman (which ostensibly adapts the first two collected volumes of the comics, Preludes and Nocturnes and The Doll’s House, as well as, in its surprise ‘bonus episode’, two out of the four stories appearing in Vol. 3 Dream Country) maintains this anthology/variety approach. It is joyous in the sense that the executive producers Allan Heinberg, David S. Goyer and Mike Barker evidently put their trust in the quality and scope of Gaiman’s original storytelling to the extent that fidelity to the comics seems to be a core guiding principle behind the adaptation (something that, it should be stated, should never be the sole criteria of value in any adaptation, but one from which readers, viewers and the adaptations themselves can never fully escape).

Additionally, it is something of a surprise given the default form of long-form serial television right now. With extended series like Breaking Bad, The Sopranos or Game of Thrones offering clear and linear narratives and a core structural trajectory – each series building exponentially in both their drama and scale toward their inevitable endgames – the idea that The Sandman as a premium TV series is unafraid to alternate between micro and macro forms of storytelling, replicating the experience of reading the original comics, is almost uniquely refreshing. The first season of the show exists somewhere between conventional serial drama of the kind referred to above, and an anthology show akin to Love, Death + Robots, Star Wars: Visions or classic series like The Twilight Zone. There are obvious points of narrative continuity, evidenced most readily in the form of Tom Sturridge’s Morpheus (AKA the titular Sandman, Dream, Lord of Dreams…) and other recurring characters including the other entities known collectively as the ‘Endless’.

But the narrative fluidity and flexibility of the first season alone – traveling through time, space, the dreaming and waking world, genre (fantasy, horror, folktale and fable) and form (live-action, animation, naturalistic and expressionistic) – results in a veritable bounty of storytelling and variety of viewer experience. There’s something for everyone, and whilst one episode’s genre or narrative conceit might not grab you as much as the last, there’s always another on the way. In its very essence, The Sandman replicates the absurd contrasts, non-sequiturs and unpredictable spirals into fantasy that dreaming itself does.

With only the last four episodes of the series (The Doll’s House arc) arguably producing the kind of cliffhanger-dependent momentum that most long-form drama demands nowadays (for recent examples, see: Severance, Black Bird, Obi-wan Kenobi) The Sandman has inevitably drawn some criticism for how it has complicated culture’s now mostly default expectation of television engagement. We have come to expect (demand?) an unrelenting assault of exponentially dramatic story communicated at often break-neck speed; a clear-cut sense of what’s important and why, and where it’s all going.

BAM: inciting incident! BAM: crisis! BAM: third act plot twist!

It is no surprise to read some critics (thankfully, a minority) describing the show as a ‘slow-rolling quest’ that presents ‘several chapters [that] are essentially episodic, at best peripherally advancing the larger plot’ (CNN.com). But why is the idea of a television show being ‘episodic’ necessarily a bad thing?

Writing in The Guardian, Charles Bramesco rightly criticises the recent trend for TV executives and marketing teams to proclaim their given show is really a 10, 20, or 74-hour movie, an active attempt to disavow the long-form serialised medium in which they work to proffer some false marker of cultural legitimacy through the promise of being ‘cinematic’. And yet, as Bramesco argues:

‘Every great TV show has found a way to tell stories contained within the space of an episode that nonetheless coalesce into a larger narrative structure. Streaming allows us to eliminate the time between instalments, [but] too many have taken that as implicit permission to abandon the building blocks of the art.’The Sandman understands its medium is television and (perhaps due to its genesis in a comics, a medium known for having to fight for cultural legitimacy and critical recognition) avoids any pretensions of so-called cinematic television or film-adjacent TV. In its truly episodic approach, The Sandman offers tightly constructed but often discrete stories that offer 45 mins – 1 hour of storytelling whilst iteratively ‘world-building’ in its further exploration of its characters and the world of ‘the dreaming’.

No, the narrative details of ‘Calliope’ or ‘Men of Good Fortune’ don’t really extend beyond their discrete durations or radically impact the macro-level narrative of The Sandman. But they’re captivating, poetic, and unforgettable examples of storytelling that have been beautifully rendered in their adaptation for Netflix. It’s why existing fans of The Sandman were unsurprised to hear the critical acclaim and first-time-viewer reaction to iconic stories such as ’24 hours’, ‘The Sound of Her Wings’ or ‘A Dream of a Thousand Cats’ because in the midst of the original comic’s grander scale, it was often these smaller individual stories which first made us fall in love with Gaiman’s world.

It’s a sign of attention to detail and world-building that the show shares with classics of prestige drama series. Yes, the sagas of Walter White or Tony Soprano play out across seasons and years and an overarching dramatic structure, but within these frameworks we get critically acclaimed standalone stories like ‘Fly’ (Breaking Bad, S3E10) or ‘Pine Barrens’ (The Sopranos, S3E11) that showcase the potential of episodic short-form storytelling. Television’s ability to facilitate these episodic tangents whilst stretching its overarching story outwards is, in my opinion, why Netflix is arguably the best platform for an adaptation of the comic. It can be allowed to stretch, grow and experiment in a way that a two-hour film adaptation (something which has been discussed in relation to Gaiman’s work since 1989) could never accomplish.

It’s why I truly hope The Sandman gets a second season (and a third, and a fourth…). Not only so we can watch beloved comic arcs like Brief Lives or Season of Mists (hinted toward in episode ten), but so we also get a chance to see other examples of Gaiman’s masterful shorter contained writing within the Sandman universe: the supernatural premiere performance of Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream, the history of the only Emperor of the USA, Joshua Abraham Norton, or a fantastical version of Baghdad and Morpheus’ involvement in its transformation.

That would be a dream come true.