‘Like I said, this is a horror story…’

So says Jamie Conklin the narrator of Stephen King’s slender novel, Later, a pulpy thriller which sees the author combine his tried and tested tropes to mostly riveting effect: a child protagonist with special powers, facing horrors originating from both the real world and the supernatural, set against a familiar historical backdrop of the early 2000s and informed by an unashamedly self-aware use of American pop-culture and gothic literature that colours so much of King’s work.

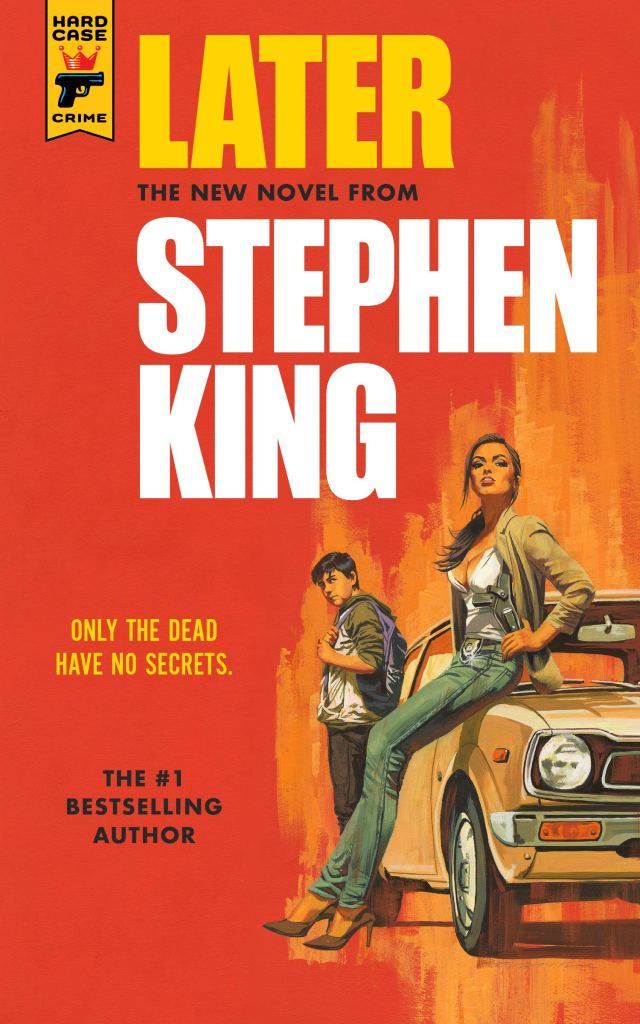

It is therefore somewhat jarring to read Later under the publishing imprint of ‘Hard Case Crime’, with its deliberately old-school illustrated cover and garish yellow colour scheme reminiscent of hard-boiled fiction of the 1930s and 1940s and the likes of James M. Cain and Raymond Chandler. There are certainly pulp crime elements to Later, although as Conklin says throughout – almost as if King were trying to continually rally against the purported boundaries of this novel’s publishing context – ‘this is a horror story’. Thematically, the novel is for the most part classic King, in the same vein as The Shining, Carrie, and perhaps more recently The Institute, rather than say the more realist storytelling of ‘Rita Heyworth and the Shawshank Redemption’ or the Mr Mercedes trilogy.

Placing these admittedly superficial inconsistencies to one side, however, Later smacks of a writer simply having fun in the kind of genre sandbox he has mastered across his expansive and prolific career.

The central premise is that Conklin, a shy and introverted kid who lives with (and arguably for) his literary agent mother, Tia, comes to learn early in his life that he can see dead people. Opening with a sequence that sees Conklin converse with an unexpectedly deceased neighbour, Mrs. Burkett, as Tia attempts to console a sobbing Mr. Burkett who breaks down at the discovery of his wife’s body, our narrator details the nature of his ‘power’ and its effect upon his young mind and perception of the world. Conklin is a smart kid, wanting to help Mr. Burkett through his loss even if he can’t articulate how he knows, for example, where his late wife’s wedding rings can be found amongst the disordered belongings she left behind. Telling his mother, who has come to believe in her son’s ability, Conklin is able to facilitate the ‘rediscovery’ of the late Mrs. Burkett’s rings when Tia suggests having a look in the cupboard. Job done. Problem solved.

Although the nature of some deaths may leave the deceased, with whom Conklin comes into contact, bloody or distressing (the bodily effect of a car accident on a pedestrian in Central Park has a particular effect on the young boy’s mind), he does not really find the phenomenon particularly frightening. Instead, Conklin accepts his unusual ability as another part of his life, one that may in fact have several uses. At its worst, it is a fact of existence to be tolerated amongst the more conventional challenges faced by an individual undergoing puberty.

That is until Tia’s police detective partner, Liz Dutton, an unpredictable and potentially dangerous force in his young life, comes to think of Conklin as a tool within her detective toolkit. The psychic-detective conceit of Later then comes into full play, perhaps the clearest embodiment of the Hard Case Crime aesthetic promised by the cover, but one that Conklin reluctantly takes on as a favour to his mother and then later, without his consent, Liz.

Later is a breezy pulp yarn that will satisfy long term fans of King, even if it comes across at times like an assortment of tropes and conventions that can be crossed off the check-list of expectations one would expect of the writer, without fundamentally changing the game or adding something wholly new to his canon. It does what it says on the tin. Like I said, this is a horror story.